Eight years ago, Washington's special envoy to Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, told former mujahideen leaders -- the likes of Marshal Muhammad Qasim Fahim and Abdul Rasul Sayyaf -- that they had a choice: either be part of the solution or the problem.

He jokingly said that Abdul Rashid Dostum, a notoriously vicious Uzbek warlord -- once aligned with the communists, later with the anticommunist mujahideen, then with the terrorist Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, and finally with the United States -- now called himself a "man of peace." That was just months after Dostum had crammed hundreds of young Pashtun men who had fought for the Taliban, many of them wounded, into unventilated train cars in searing heat. Dozens of them died before arriving at their final destination: a grossly overcrowded prison in his stronghold in the northern province of Sheberghan. By then, Dostum had become Washington's new best friend.

Over five years ago, I argued in a Foreign Affairs essay ("Afghanistan Unbound," May/June 2004) that the windows of opportunity were closing for Afghanistan and that making allies of Afghans -- not military action -- would win what was then a losing war. I wrote then that the alliances the United States and its coalition partners had made with Afghan warlords, whose internecine fighting had killed 50,000 of their own people when they were last in power, were returning Afghanistan to its lawless and insecure pre-Taliban days. Choosing to ignore the warlords' past crimes, I argued, would embolden them, instead of making them the good partners the West so naively believed they could be. Washington would not meet its goal of greater homeland security, and for Afghans, peace and prosperity would remain elusive.

Indeed, as the United States and its NATO allies slog on in Afghanistan, it is Washington's mismanagement of local alliances that has proved to be the undoing of its strategy in the country. And, most damaging, these mistakes have cost the United States the allegiance of ordinary Afghans -- an allegiance that is critical to winning the war, collecting intelligence to find al Qaeda, and ensuring that Afghans themselves prevent whoever is in power, including the likes of Sayyaf, from using their country as a safe haven.

The light footprint strategy, which called for less rather than more foreign intervention and was sanctioned by the United Nations and the West following the collapse of the Taliban, failed to take into account that a post-Taliban Afghanistan was a country without institutions, leaving a leadership vacuum that could only be filled with the cadre of leaders that had emerged from 30 years of war -- fighting men who ruled by the power of the gun.

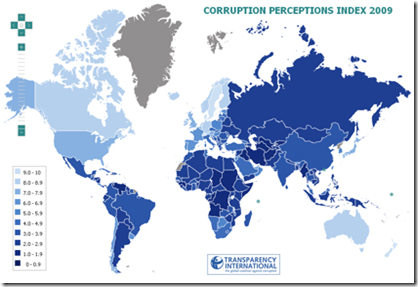

That rule has returned: Afghanistan today looks a lot like the Afghanistan of 2004, only a little bit worse. It also resembles the pre-Taliban Afghanistan of 1995 and 1996, when venturing on just about any highway was a risk and visiting a government office required a pocketful of bribes. The only difference between then and now is that the Afghan factions are no longer firing at each other and killing civilians who get caught in the middle. That is now being done by the Taliban and the international forces.

It was implied by Khalilzad that there would be consequences if the former mujahideen-cum-post-Taliban leaders did not play by the rules and work to make Afghanistan a functioning, albeit fragile, democracy. That never happened, and, so far, the consequences for the culprits are difficult to see. But the effects of their rise to power have been excruciatingly clear to Afghan

citizens.

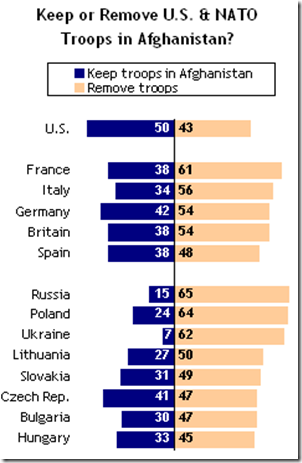

As U.S. President Barack Obama tries to steer a new course in Afghanistan, there are grumblings in the international community that its allies in Afghanistan are not up to the mark. Yet it is unclear whether anyone appreciates the seriousness of the problem and how it goes to the heart of a successful strategy. Success in Afghanistan is much more than simply establishing good governance or cleaning up the façade.

It is not just the big-name ex-mujahideen such as Fahim (who has been accused of drug dealing and massive corruption) or Sayyaf (whose men actually brought Osama bin Laden to Afghanistan and, under Sayyaf's guidance, raped and scalped women) who have given strength to the Taliban. Appointments at every level -- right down to the district level -- have done so, too, disillusioning even the most optimistic of Afghans. They have made talk of negotiations with so-called moderate insurgents a nonstarter, as even the most moderate among them face no incentive to be part of such an unpopular regime. These appointments and allegiances, brokered by the international community, have frustrated Afghans and eroded their trust and hope.

Take Musa Qala, a district in the southern province of Helmand, for example. Controlled by the Taliban and retaken by the British in December 2007, Musa Qala provides a glimpse of the difficulties that face the international troops who, eight years on, are still struggling to navigate their way through a country, culture, and population that have many puzzling layers. Just before the British swept into the district, a Taliban commander, Maulvi Abdul Salam, switched sides and joined the anti-Taliban forces, apparently the result of months of negotiations. For his defection he was made governor of Musa Qala.

Since then, news reports have alternately described Salam as "unknown" or "mysterious." Perhaps he was unknown to the international community or to the British who appointed him governor, but to Afghans he was not. Salam's reputation stretches back more than a decade for area residents. Some of them recall his killing of the dozens of prisoners he took in 1994, when the Taliban first emerged as a fighting force, and when he headed west toward the city of Herat to throw out another warlord, Ismail Khan (now a key U.S. ally, too). Salam is an example of the so-called moderates willing to join with the current government, the United States, and NATO -- but who only serve to strengthen the Taliban.

Since Salam was appointed governor, the elders of Musa Qala have accused him of widespread corruption, mismanagement, and abuse, and have petitioned for his removal. His wink-and-nod attitude to the corrupt practices of his administration has strengthened the Taliban, which has set up a court that now operates in the area every Thursday, dispensing justice to the dozens who come before it.

Thus, even as nearly 100,000 U.S. and NATO troops swarm around Afghanistan, the Taliban are running regular weekly courts. In Musa Qala, the Taliban have even set up two judicial committees to assist their court -- one to ensure the judgments are enforced, the other to guarantee the judge stays honest. One Taliban judge who was caught taking a bribe was publicly humiliated and then fired for his misdeeds.

In southern Kandahar, just two days before the August elections, a young man from Musa Qala told the story of the Taliban courts. He had campaigned for Afghan President Hamid Karzai in 2004 and had honed his English believing it would improve his future. But in 2009, on the eve of much touted elections, he was brimming with anger at an international community whose foolhardy alliances -- made out of ignorance or expediency -- have made even him speak of the Taliban courts with admiration.

When the Taliban were driven from power, Afghans from across the country wanted to be allies of the international community, happy to see the back of the wretched Taliban regime. Eight years on, most people, including the young man from Musa Qala, are fed up. They see their country heading for destruction, led by corrupt and conniving leaders enabled by an international community unable to figure out the good guys from the bad guys.

Not long ago in Kabul, an Afghan friend who has stayed in his homeland through the communists, the mujahideen, and the Taliban, and who was always certain of a better day, told me that his optimism had run out. "I want out," he said. "You always wondered at how I could always be so optimistic, and now it's gone."

That's a sad epitaph for the loss of eight years and countless lives.

In Afghanistan, making allies of the population is the ticket to success. But that will not come while the international community remains aligned with the very warlords who are making Afghans' daily lives so difficult; while Bagram jail holds as many as 600 men, barely a fraction of whom were actually picked up on the battlefield; while errant bombs kill civilian targets incorrectly identified by allies who go unpunished for their errors.

It is a difficult road ahead for Obama as he struggles with a new Afghan strategy, but it is an even more difficult road ahead for Afghans who struggle to survive the United States' and the international community's mistakes.

Copyright © 2002-2009 by the Council on Foreign Relations, Inc.