Watch how journalists at Guardian used the data to paint a hitherto hidden picture of the Afghan war.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/datablog/interactive/2010/jul/26/ied-afghanistan-war-logs

Watch how journalists at Guardian used the data to paint a hitherto hidden picture of the Afghan war.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/datablog/interactive/2010/jul/26/ied-afghanistan-war-logs

Do Muslims have an image problem? The western media is reporting that a poor image of Pakistan may be behind the lacklustre response to fund raising appeals to support rescue efforts. The widespread coverage of violent protests against western countries on the streets of Pakistan has indeed helped generate a negative stereotype of Pakistan.

While we may not be able to quantify how the rest of the world views Pakistan, we may still be able to tell what people think of Muslims in general, who may have a high opinion of themselves, but the more important question to explore is how does the rest of the world see Muslims?

The Pew Global Attitudes Project conducts opinion polls about matters of global interest. The opinion poll conducted in spring 2009 carried a question about what opinion people had of Muslims. The question was put to 20,000-plus respondents in 25 countries, including some Muslim majority countries. I got hold of the raw dataset, which I analyzed to determine if people held a favourable or unfavourable opinion of Muslims.

As expected, Muslims living in Muslim majority countries indeed had a very high opinion of themselves. However, a very large segment of respondents from Muslim minority countries reported having somewhat or very unfavourable view of Muslims. No fewer than 42% respondents hailing from Muslim minority countries reported unfavourable opinion of Muslims. On the other hand, only 10% respondents from Muslim majority countries reported unfavourable opinion of Muslims.

The graph below indicates that Egyptians, Indonesians, Lebanese and Pakistanis have the most favourable opinion of Muslims, as is indicated by the green colour bars. Over 90% of the respondents in these countries reported a favourable opinion of Muslims. Not much surprise there.

On the other hand, the least favourable, or most unfavourable, view of Muslims was recorded in Israel where almost every four in five respondents reported an unfavourable opinion of Muslims. Surprisingly, the second highest unfavourable view of Muslims was reported in China where 65% respondents held an unfavourable opinion of Muslims. While the Pakistanis may think of China as a steadfast friend, only 16% Chinese reported favourable opinion of Muslims.

Also surprising is the fact that 56% Japanese held an unfavourable opinion of Muslims. India is another country where the majority (greater than 50% of the respondents) reported an unfavourable opinion of Muslims. Japan seems an anomaly because unlike China, India, and Israel, which have territorial disputes with Muslim minorities, Japan has no such outstanding disputes involving Muslims. Similarly, 48% South Koreans, who hold an unfavourable opinion of Muslims, seem odd as well because South Koreans do not have any direct conflict involving Muslims. However, South Koreans could have been incensed by the fact that most Muslim countries, including Pakistan, have shoddy dealings with DPRK, South Korea’s archrival.

It appears that Latin American countries are the most ignorant of Muslims where 42% respondents in Argentina, 38% respondents in Mexico, and 20% respondents in Brazil did not have any opinion about Muslims. Since a large number of respondents in Latin American countries expressed ignorance about Muslims, these countries therefore reported the lowest favourable (not necessarily unfavourable) opinion of Muslims amongst the Muslim minority countries.

France with 63% favourable opinion of Muslims had the highest favourable view of Muslims amongst Muslim minority countries followed by Great Britain, Canada, Kenya, Russia, and United States. Almost 61% respondents in Canada and 59% respondents in the United States reported a favourable opinion of Muslims. Unlike other countries listed here, Canada and the United States stand out for their favourable opinion of Muslims. While France and Great Britain are home to sizable Muslim populations, the same is not true for the United States and Canada, and therefore a large proportion of population reporting favourable opinion of Muslims represents the views of non Muslims Canadians and Americans.

Amongst Muslim majority countries, Turkey and Palestinian Territories standout for having an unexpectedly high unfavourable view of Muslims. Almost one in five respondents in Turkey and Palestinian Territories reported an unfavourable view of Muslims. The determinants of this self hate phenomena could be of great interest to social scientists.

So the short answer to the question if Muslims have an image problem is yes. This is evident from the fact that almost 42% respondents in Muslim minority countries reported unfavourable opinion of Muslims. The long answer to the same question is also yes, but it comes with a caveat. Whereas Muslims are, to a large extent, responsible for their poor image, those who create that image in the west also share some blame.

The electronic and print media plays a big role in shaping opinions in the west. To a very large extent, western audiences form their opinions from what they learn from the mainstream news media. Thus the 6:00 pm news telecast goes a long way in shaping public opinion in western countries.

It has always been convenient for the western journalists visiting Muslim majority countries to focus their cameras on fire-breathing, flag burning crowds of bearded, mostly unemployed, youths marching down the urban streets. The fact that almost 50% of the population in most Muslim countries is under the age of 25, along with being unemployed, poorly educated, frustrated, and disenfranchised by political and military regimes, it should not come as a surprise that streets in Muslim majority countries routinely become scenes of violent protests.

But what about those who live in the heartland in the same Muslim majority countries. To date, most Muslim majority countries are largely rural with fewer than 35% population residing in urban centres. What do the rural youths in Muslim heartland think? What are their aspirations, fears, and hopes?

We don't know the answer to these questions because finding those answers would require journalists to visit the rural landscapes in Muslim majority countries. There they may not find violent protests against the west, but instead they may find daily struggle to survive in good times, and the hopes to one day be able to rebuild after natural disasters.

These scenes of struggle to make the ends meet may not generate the sensational footage needed for the 6:00 PM telecasts.

The claim that the western journalists stay cocooned in five star hotels and do not explore the countryside, where most Muslims live, may sound exaggerated. However, I have numbers to prove my case. Consider The New York Times, a premier news outlet that prints “All the News That's Fit to Print.” In 2009, NYT published 286 stories filed from within Pakistan. Out of those 286 stories, 63% stories were filed from the federal capital, Islamabad. Another 14% stories were filed from Peshawar, the provincial capital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and 8% stories were filed from Lahore, the provincial capital of Punjab. The correspondents for New York Times filed only 15% stories from places other than Islamabad, Lahore, and Peshawar, a fact I illustrate in the following graphic.

This is certainly odd. The combined population of Islamabad, Lahore, and Peshawar is less than 8 million in a nation of 170 million. However, the New York Times files 85% of its stories in Pakistan from a population base of just 5%. Other western media active in Pakistan is no different. I would call this lazy journalism, which has dreadful consequences as could be seen from the lack of sympathy in the west for flood-soaked Pakistanis.

So yes, Muslims do have an image problem, however it would help if the western journalists trek farther than the lobbies of luxury hotels in cities, and seek out the common Muslim man or woman in the rural heartland, rather than always calling on the demagogues in Muslim majority countries, who compete with each other in making the most outrageous statements against the west.

As a result of my meetings with French President Nicolas Sarkozy and British Prime Minister David Cameron, the plight of Pakistan's flood victims is receiving full international attention. The British government pledged $24 million in aid. The U.S. government, with which I was in touch by telephone, has pledged $35 million in relief funds and made helicopters available for rescue efforts. The NATO coalition, at war in neighboring Afghanistan, has also offered help, as have major European nations and Japan.

My visit to Britain, an important ally in fighting terrorism, also helped defuse potential political friction over Mr. Cameron's remarks in India ostensibly criticizing past Pakistani policy on jihadist militancy. And it allowed me to reaffirm to the relatively new British government Pakistan's commitment to fighting all terrorist groups.

After a decade of suffering the political, economic and social abuses of military dictatorship, Pakistan has spent the last two years re-establishing our democratic infrastructure and rebuilding our national character and cohesiveness.

Our project of national renewal is even more difficult because we are on the front lines of the battle against international terrorism. In particular, we live with the effects of the historical errors of the 1980s that have come back to haunt the world. The use of jihad in Afghanistan as the blunt instrument to destroy the Soviet Union certainly had short-term benefits. But the decision to empower the most radical elements of the mujahideen—and then to abandon Afghanistan economically, politically and militarily after 1989—set the stage for the dreaded clash of civilizations that has plagued the world since.

Whatever horror the Western world has faced at the hands of extremists acting in the name of Islam pales in comparison to the nightmare endured by the people and government of Pakistan. Terrorists have killed more Pakistani soldiers than NATO coalition troops fighting in Afghanistan. Pakistan has lost 2,000 police in the war on terror, more than all other countries combined. And we have lost almost 6,000 civilians, twice the number who died in the World Trade Center.

We have also lost our country's greatest recent political leader—my wife, Benazir Bhutto. My wife's death was even more shocking than the United States losing a president or Britain its prime minister, because she defined our democratic consciousness in the face of dictatorship. She was a symbol of hope to tens of millions in my country—and hundreds of millions around the world—that there could be a better future ahead for our children.

As I return to Pakistan, I bring back tangible results that will help the flood victims in the short run and lay the foundations for national recovery in the long run. I might have benefitted personally from the political symbolism of being in the country at the time of natural disaster. But hungry people can't eat symbols. The situation demanded action, and I acted to mobilize the world.

Now the work must continue. I call on the generous people of the United States to rise to this occasion as they have countless times over the last two centuries. Pakistan welcomes your contributions, as individuals and by your government.

Mr. Zardari is the president of Pakistan.

-----

Judicial Coup in Pakistan

Once a democratic champion, the Chief Justice now undermines the elected government.

By DAVID B. RIVKIN JR. AND LEE A. CASEY

When U.S. President Barack Obama sharply challenged a recent Supreme Court decision in his State of the Union address, prompting a soto voce rejoinder from Justice Samuel Alito, nobody was concerned that the contretemps would spark a blood feud between the judiciary and the executive. The notion that judges could or would work to undermine a sitting U.S. president is fundamentally alien to America's constitutional system and political culture. Unfortunately, this is not the case in Pakistan.

Supreme Court Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammed Chaudhry, the country's erstwhile hero, is the leading culprit in an unfolding constitutional drama. It was Mr. Chaudhry's dismissal by then-President Pervez Musharraf in 2007 that triggered street protests by lawyers and judges under the twin banners of democracy and judicial independence. This effort eventually led to Mr. Musharraf's resignation in 2008. Yet it is now Mr. Chaudhry himself who is violating those principles, having evidently embarked on a campaign to undermine and perhaps even oust President Asif Ali Zardari.

The first is a decision by the Supreme Court, announced and effective last December, to overturn the "National Reconciliation Ordinance." The NRO, which was decreed in October 2007, granted amnesty to more than 8,000 members from all political parties who had been accused of corruption in the media and some of whom had pending indictments.Any involvement in politics by a sitting judge, not to mention a chief justice, is utterly inconsistent with an independent judiciary's proper role. What is even worse, Chief Justice Chaudhry has been using the court to advance his anti-Zardari campaign. Two recent court actions are emblematic of this effort.

While some of these people are probably corrupt, many are not and, in any case, politically inspired prosecutions have long been a bane of Pakistan's democracy. The decree is similar to actions taken by many other fledgling democracies, such as post-apartheid South Africa, to promote national reconciliation. It was negotiated with the assistance of the United States and was a key element in Pakistan's transition from a military dictatorship to democracy.

Chief Justice Chaudhry's decision to overturn the NRO, opening the door to prosecute President Zardari and all members of his cabinet, was bad enough. But the way he did it was even worse. Much to the dismay of many of the brave lawyers who took to the streets to defend the court's integrity last year, Mr. Chaudhry's anti-NRO opinion also blessed a highly troubling article of Pakistan's Constitution—Article 62. This Article, written in 1985, declared that members of parliament are disqualified from serving if they are not of "good character," if they violate "Islamic injunctions," do not practice "teachings and practices, obligatory duties prescribed by Islam," and if they are not "sagacious, righteous and non-profligate." For non-Muslims, the Article requires that they have "a good moral reputation."

Putting aside the fact that Article 62 was promulgated by Pakistan's then ruling military dictator, General Zia ul-Haq, relying on religion-based standards as "Islamic injunctions" or inherently subjective criteria as "good moral reputation" thrusts the Pakistani Supreme Court into an essentially religious domain, not unlike Iranian Sharia-based courts. This behavior is profoundly ill-suited for any secular court. While Article 62 was not formally repealed, it was discredited and in effect, a dead letter.

The fact that the petitioner in the NRO case sought only to challenge the decree based on the nondiscrimination clause of the Pakistani Constitution and did not mention Article 62 makes the court's invocation of it even more repugnant. Meanwhile, the decision's lengthy recitations of religious literature and poetry, rather than reliance on legal precedent, further pulls the judiciary from its proper constitutional moorings.

The second anti-Zardari effort occurred just a few days ago, when the court blocked a slate of the president's judicial appointments. The court's three-Justice panel justified the move by alleging the president failed to "consult" with Mr. Chaudhry. This constitutional excuse has never been used before.

It is well-known in Islamabad that Mr. Zardari's real sin was political, as he dared to appoint people unacceptable to the chief justice. Since consultation is not approval, Mr. Chaudhry's position appears to be legally untenable. Yet Mr. Zardari, faced with demonstrations and media attacks, let Mr. Chaudhry choose a Supreme Court justice.

There is no doubt that the chief justice is more popular these days than the president, who has been weakened by the split in the political coalition which brought down Mr. Musharraf. Former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is now a leading opponent of the regime. There is a strong sense among the Pakistani elites that Justice Chaudhry has become Mr. Sharif's key ally.

The fact that Mr. Chaudhry was a victim of an improper effort by former President Musharraf to replace him with a more pliant judge makes his current posture all the more deplorable. His conduct has led some of his erstwhile allies to criticize him and speak of the danger to democracy posted by judicial meddling in politics. The stakes are stark indeed. If Mr. Chaudhry succeeds in ousting Mr. Zardari, Pakistan's fledgling democracy would be undermined and the judiciary's own legitimacy would be irrevocably damaged. Rule by unaccountable judges is no better than rule by the generals.

Messrs. Rivkin and Casey, Washington, D.C.-based attorneys, served in the Department of Justice during the Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations.

The following data are available from icasualties.org.

Chris Alexander, Canada’s former ambassador in Afghanistan, paints a false picture of Afghanistan in the Globe and Mail on Saturday by suggesting that "Afghan society has recovered smartly since 2001." To bolster his point he mentions that despite the global recession, Afghanistan's GDP grew by 22%. This indeed is a gross misrepresentation of Afghanistan's economy and society, which have literally collapsed in the past decade.

The World bank also noted that 75% of the foreign aid bypasses the Karzai government's budget system, making the government less legitimate and relevant to the Afghans.

Mr. Alexander also suggests that Afghanistan’s inflation “has been minus 12 percent.” This again is not only false, but poorly stated. By all accounts, inflation in Afghanistan has hovered around 30%, which has subjected poor Afghans, who make up the majority of the population, to extreme financial hardships. The recent estimates of a lower inflation does not apply to cities, such as Kabul, where ordinary Afghans can no longer afford to pay rents for even modest accommodation.

By suggesting that Afghanistan's economy is rapidly growing (which is also not factual), Mr. Alexander is in fact concealing the fact that the country is becoming increasingly dependent on charity, and on billions in debt forgiveness from the IMF.

Such misrepresentation of facts is tantamount to intellectual dishonesty, to say the least.

Torrential rains have killed 400 and displaced another half a million in Pakistan. A nation devastated by senseless violence, suicide attacks, indiscriminate bombings from American drones, and a collapsed economy is now facing another natural disaster. The pictures below from BBC show that the victims of this national disaster is again the poorest in Pakistan.

Pakistani society and economy has been brought to the brink of disaster by the NATO’s demands to wage a war against its own people. With hundreds of thousands of troops engaged in the American war against terror on the western borders, and another few thousands stationed along the Indian border, the military and civilian establishment in Pakistan does not have the capacity to cope with even mild disasters, let alone a major flood, which is wreaking havoc in northern Pakistan.

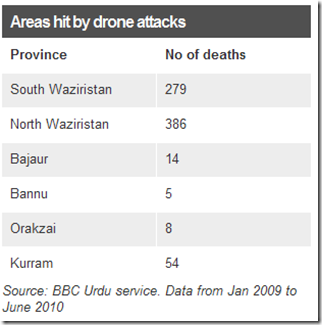

BBC has recently pointed out that the drone attacks in Pakistan under the Obama administration have increased manifolds. These pilot-less, remotely controlled aircrafts have been successful in killing key militants in Pakistan. However, these attacks have killed scores of innocent Pakistani tribesmen, which has resulted in a widespread opposition against the drone attacks in Pakistan.

The US government under President Obama intensified the use of drones in Pakistan. This comes as  a surprise to many in both the United States and in Pakistan who naively believed that a change in White House implies a change in the Pentagon. The graph below however suggests that President Obama`s and installations in fact more trigger happy than the one it replaced.

a surprise to many in both the United States and in Pakistan who naively believed that a change in White House implies a change in the Pentagon. The graph below however suggests that President Obama`s and installations in fact more trigger happy than the one it replaced.

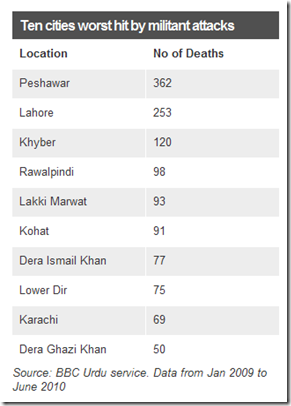

The attacks by the militants on military forces and civilians in Pakistan, and drone attacks and other offenses launched by the Pakistani military against the militants have ended up in a tit-for-tat killing game in Pakistan, which is slowly but surely destroying the social, cultural, and economic fabric of the country.

|  |