Saturday, July 31, 2010

GDP growth in South Asia

Nineties were the decade when India and Bangladesh picked up pace and started to strengthen their economic development based on the innovation and technical prowess of the graduates from their engineering and business schools. India picked up a faster pace of economic development in the early nineties and Bangladesh by mid nineties, leaving Pakistan trailing behind in economic growth.

Pakistan, on the other hand, spent the nineties in a battle for power between the military, politicians, and the bureaucracy. It resulted in a lost decade. No real economic or social development transpired in Pakistan. Furthermore, by creating and unleashing the Taliban, Pakistan also sealed the fate for Afghanistan, which has suffered much more than Pakistan in the past 15 years.

Floods kill over 400, displace another half a million in Pakistan

Torrential rains have killed 400 and displaced another half a million in Pakistan. A nation devastated by senseless violence, suicide attacks, indiscriminate bombings from American drones, and a collapsed economy is now facing another natural disaster. The pictures below from BBC show that the victims of this national disaster is again the poorest in Pakistan.

Pakistani society and economy has been brought to the brink of disaster by the NATO’s demands to wage a war against its own people. With hundreds of thousands of troops engaged in the American war against terror on the western borders, and another few thousands stationed along the Indian border, the military and civilian establishment in Pakistan does not have the capacity to cope with even mild disasters, let alone a major flood, which is wreaking havoc in northern Pakistan.

A man trying to save minors from the flood

A child trying to salvage what is left of his home

Men trying to flee the flood-stricken areas. What happened to the women and children?

Related articles by Zemanta

- Monsoon floods kills 430 in Pakistan (seattletimes.nwsource.com)

- At least 325 people dead in Pakistan flooding (cnn.com)

- Pakistan floods kill more than 400 (nationalpost.com)

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Taliban are gaining ground in Pakistan, again

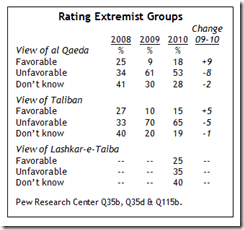

Make no mistake, the Taliban are regaining ground in Pakistan, at least in the court of public opinion. A recent survey has revealed a dramatic 50% increase in a favourable view of the Taliban in Pakistan.

The results from a survey of 2,000 adult (mostly urban) Pakistanis, conducted in April 2010, have revealed that 15% Pakistanis had a favourable view of the Taliban, up from 10% in 2009. At the same time, 65% Pakistanis expressed unfavourable view of Taliban, which was down from 70% in 2009. The survey was conducted by Pew Global Attitudes Project, which is based in Washington, DC.

Al-Qaeda has in fact seen even a more dramatic increase in its popularity in Pakistan. The number of Pakistanis having a favourable view of al Qaeda doubled from 9% in 2009 to 18% in 2010. At the same time those having an unfavourable view of al Qaeda declined from 61% in 2009 to 53% in 2010. Concomitantly, Pakistanis are becoming less concerned about the threat of extremist groups taking control of Pakistan. This is happening even when there is no real change in threats faced by Pakistanis.

These are indeed troubling trends. At the time when Pakistan is facing grave economic, social, and security challenges, militant extremists are gaining popularity in Pakistan. This is probably an outcome of the failed governance by the federal, provincial, and local governments, which has resulted in massive unemployment, high inflation, and a complete breakdown of civil infrastructure.

It should come as no surprise that most Pakistanis believe that the current economic situation is indeed ‘very bad’. 78% Pakistanis had a very unfavourable view of the economic situation in 2010, up from 32% in 2007. What is even more alarming is that the number of those who worry about the future economic conditions in Pakistan has increased over 200% from 2008, when only 16% expressed worries about future, compared to one in two Pakistanis in 2010.

This does not bode well for the democratic forces in Pakistan. The polls suggest that the masses view economy performing better under a military dictator (General Musharraf) than under democratic setups. These facts are not lost on the military, which has perhaps gained the most from the gory chaos in Pakistan. The military has regained its popularity since its reputation was dragged in mud by the actions taken by General Musharraf against the Supreme Court in 2007. No fewer than 84% Pakistanis in 2010 believed that the military had a good impact on their country. Pakistani politicians should learn a thing or two from the military, or for that matter al Qaeda, about how to stay popular amongst Pakistanis.

While the military may have regained its popularity, fewer than one-half of Pakistanis support military action against the Taliban in Pakistan's tribal areas. Another 20% Pakistanis in fact oppose any military action against the Taliban.

While the militants are gaining ground in popularity, popularity of the political leadership in Pakistan has taken a nosedive. Consider president Zardari, who was viewed favourably by 64% Pakistanis in 2008, is now viewed favourably by no more than one in five of his fellow countrymen. Even within his own party, i.e., the Pakistan People's Party, his popularity at 38% suggests that he is fast losing ground even amongst his own political base.

In an earlier blog, I have charted (see the graph below) the unpopularity index for president Zardari, which showed that he became increasingly unpopular starting fall 2009.

With President Zardari fast becoming a dark horse in this political race, other political players are slowly gaining ground in Pakistan. The leader of the opposition, Mian Nawaz Sharif, is the most favourably viewed politician in Pakistan where 71% reported having a favourable view of him. Also viewed favourably is the current chief justice of the supreme court, as well as the cricketer-turned-politician, Imran Khan.

The Pakistanis (civilians and military alike) continue to be obsessed with India with over 53% having the view that India poses the greatest threat to Pakistan. The Taliban at 23% and al Qaeda at 3% lag far behind India in ordinary Pakistanis' threat perception. This skewed view of reality is perhaps behind Pakistan military's plans to continue engaging with the Taliban to gain their ‘strategic depth’ against India. This flawed policy has brought Pakistan to an economic, social, and moral disaster.

Given the unpopularity of drone attacks and the military action in tribal Pakistan, it comes as no surprise that only a tiny minority in Pakistan regards president Obama favourably. Fewer than 8% Pakistanis expressed confidence in president Obama, whereas 17% Pakistanis held a favourable view of the United States. Not all is lost for the United States and Pakistan. A very large number of Pakistanis, 64% to be precise, expressed their desire to improve relations between Pakistan and the United States.

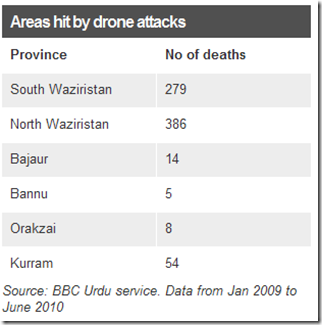

The United States should review these trends objectively and consider abolishing policies and actions that have made president Obama unpopular in Pakistan. The suspension of drone attacks alone would go a long way in improving president Obama’s image in Pakistan. Given the limited success of drone attacks, and the large number of civilian casualties that has resulted from such attacks, the United States should not be too concerned in stopping drone attacks, which also constitute a violation of international law.

While stopping drone attacks will help improve America’s image in the region, nothing short of a complete withdrawal of NATO troops from the region would achieve resumption of normalized relations between South Asia and the United States. Fewer than 7% Pakistanis favoured keeping NATO troops in Afghanistan until the security situation would improve. An overwhelming majority of 65% Pakistanis would like to see NATO leave Afghanistan sooner than later.

The political leadership in Pakistan should realize that time is fast running out on them. Their political fortunes are collapsing, and those of the militants and the military are fast rising. The scandal about parliamentarians with fake academic degrees has damaged the already compromised reputation of politicians in Pakistan. Political parties of all stripes have been dragging their feet in eradicating fraudulent politicians with fake academic degrees from their cadres. Such lack of moral integrity in the political spheres in Pakistan is behind the improving outlook of the both the militants and the military.

It would indeed be a sad day in Pakistan if the military would ride back into power, again unsettling the democratic setup in Pakistan. By losing the trust of their fellow countrymen, politicians will partially be responsible, if not completely, for derailing democracy in Pakistan.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Pakistan 'less afraid of Taliban' (bbc.co.uk)

- Poll: Nearly 6 in 10 Pakistanis view US as enemy (sfgate.com)

- Wikileaks and the ISI-Taliban nexus | Peter Galbraith (guardian.co.uk)

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

WikiLeaks, Pakistan, and ISI

Image via Wikipedia, Cobra helicopters at Multan Air base

The recent release of Afghan war documents by WikiLeaks has supposedly exposed the links between Pakistan Army and the Taliban. This has apparently concerned many in the US and Canada making it the front page news in The New York Times and the Globe and Mail. The western governments’ reaction carries a strange element of surprise on the discovery of links between Pakistan’s intelligence agency, the ISI, and the Taliban.

Any surprise on such news is unwarranted. The ISI was paid handsomely by the United States and Saudi Arabia over the past three decades to develop alliances and networks with the radical religious elements in the tribal areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan to raise an army of mercenaries to fight the Soviet Army. They were called the Mujahedeen then and were held in equal esteem as the founding fathers of America by former President Reagan.

“These gentlemen are the moral equivalents of America’s founding fathers.” — Ronald Regan while introducing the Mujahedeen leaders to media on the White house lawns (1985).

Source: Political Enquirer

The correct term for Mujahedeen now is Taliban, and those who praised the Mujahedeen’s armed struggle from the Soviets as the fight for freedom are now denouncing their fight against NATO. The White House has made a radical shift from that day in 1985 when President Reagan declared the visiting Mujahedeen from Afghanistan the moral equivalents of America’s founding fathers.

America’s war against Soviet Union was fought by Afghans and Pushtuns from Pakistan and was engineered by the ISI. Over the years the ISI has used the vast supply of undocumented funds from the United States and Saudi Arabia to create a network of agents that run from Afghanistan to Central Asia and beyond. ISI considers itself a serious player in the region and would like to see even a bigger role for itself in conflicts in its backyard as well as the remote hotspots in the Middle East and the Balkans.

Many have opined that the US is not pleased with the continued linkages between the Taliban and the ISI. This is comical to say the least. As early as in 2006, if not sooner, the US asked the Saudis to arrange dialogue with the Taliban to plan an exit strategy from Afghanistan. Talks were held between the Saudis, Americans, and the Taliban in Saudi Arabia. ISI made those talks happen.

Americans are literally blind in Afghanistan without the ISI. The Wiki Leaks documents reveal the shoddy intelligence that the US managed on its own without the ISI. It is indeed alarming to see the poor quality of intelligence on which the Americans planned their Afghan strategy.

The ISI has been aware of its importance in the region. It knows well that it has monopoly on intelligence, militant networks, and logistics in the region for any actions planned in Afghanistan. It is in no hurry to severe its ties with the Taliban, whom the ISI plan to use not only in the short-run, but in the longer run to deal with scenarios that will emerge after the likely haphazard withdrawal of the NATO forces from Afghanistan. This may happen in 2014 or sooner, and the ISI would like to be ready for the day that happens.

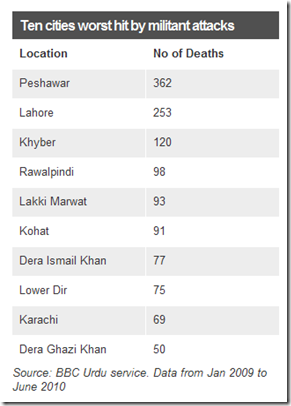

The civilians in Afghanistan and Pakistan are likely to be in the eye of the violent storm in the months and years to come. NATO’s war against Taliban has essentially become the war against Pushtuns. The fact that the NATO is siding with the Northern Alliance, which consists of non-Pushtun minorities in Afghanistan, is not lost on Pushtuns in Afghanistan and Pakistan, who see this war increasingly as a war against Pushtunss and yes, Islam. Their reaction therefore is equally violent if not more as the one they are subjected to. The US continues to drop bombs from unmanned aircrafts in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Taliban continue to orchestrate suicide bombings, the latest of which killed seven earlier today in Pabbi, near Peshawar.

I am reminded of the stories my grandmother told me of the picnics she had with her children near the river in Pabbi or the outings she had been to with her children in Peshawar. By the time I grew up, Peshawar had gone through numerous prolonged phases of violence and chaos. There were no picnics or outings; instead there were bombs and target killings.

The sorry saga continues in Peshawar, Pabbi, Nokhar, Waziristan, Kurrum Agency, and in the rest of Pakistan. The US, Canada, and the rest of NATO is now mulling over an exit strategy in Afghanistan. My family in Peshawar is not that fortunate. They have nowhere to go and survive this and other impending crises in the region. While NATO devises an exit strategy, my family worries about its survival strategy.

Related articles by Zemanta

- Wikileaks and the ISI-Taliban nexus | Peter Galbraith (guardian.co.uk)

- Pakistani spy agency denounces leaked U.S. intelligence reports (theglobeandmail.com)

- Editorial: Pakistan's Double Game (nytimes.com)

- Pakistan slow to break with Taliban, U.S. says (reuters.com)

- The AfPak Papers (online.wsj.com)

- Charlie Wilson's War (eschatonblog.com)

Saturday, July 24, 2010

Love parade meets Indian stampedes

A stampede at love parade, a summer festival in Duisburg, Germany, resulted in the death of 18 people caught in a tunnel. Over one million people were celebrating the festival.

Unlike Germany, where this is a first event of its kind in the recent past, such unfortunate accidents are common in India. In Utter Pardesh in India, 63 people died at a temple. Numerous other similar incidents of stampedes resulting from panic or collapsed bridges are common in the developing countries where very large gatherings are common.

Love Parade is one of the biggest gatherings in Europe. As the number of people at an event runs into millions, the odds for such accidents increase, regardless of the location of such events.

Related articles by Zemanta

- At Least 15 Killed In Love Parade Stampede (news.sky.com)

- Indian officials: Stampede kills five (cnn.com)

Obama and drones: the continuation of a failed, immoral policy

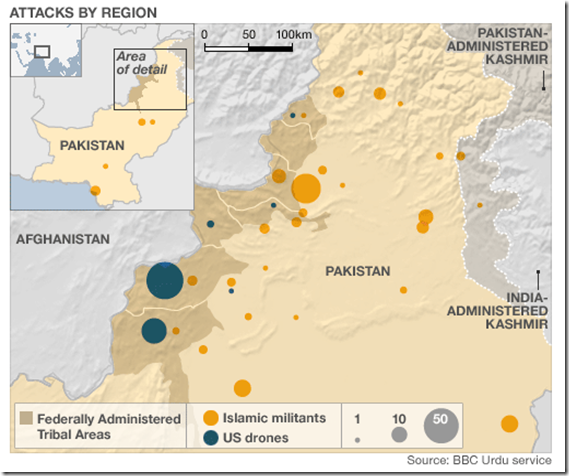

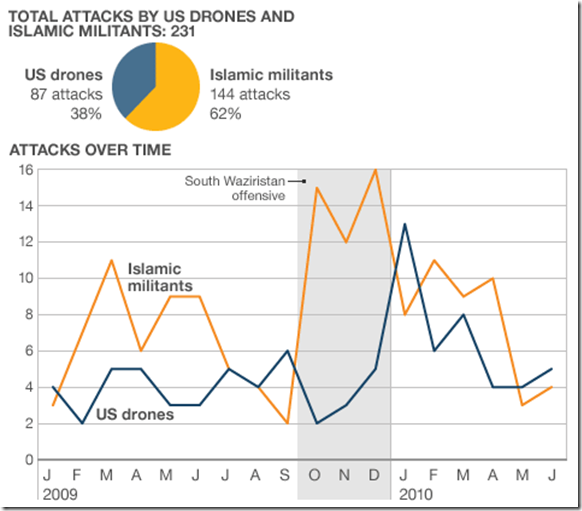

BBC has recently pointed out that the drone attacks in Pakistan under the Obama administration have increased manifolds. These pilot-less, remotely controlled aircrafts have been successful in killing key militants in Pakistan. However, these attacks have killed scores of innocent Pakistani tribesmen, which has resulted in a widespread opposition against the drone attacks in Pakistan.

The US government under President Obama intensified the use of drones in Pakistan. This comes as  a surprise to many in both the United States and in Pakistan who naively believed that a change in White House implies a change in the Pentagon. The graph below however suggests that President Obama`s and installations in fact more trigger happy than the one it replaced.

a surprise to many in both the United States and in Pakistan who naively believed that a change in White House implies a change in the Pentagon. The graph below however suggests that President Obama`s and installations in fact more trigger happy than the one it replaced.

The attacks by the militants on military forces and civilians in Pakistan, and drone attacks and other offenses launched by the Pakistani military against the militants have ended up in a tit-for-tat killing game in Pakistan, which is slowly but surely destroying the social, cultural, and economic fabric of the country.

|  |

Related articles by Zemanta

- Drone strike in Pakistan kills 16 (cnn.com)

- The drone war in Pakistan (theworld.org)

- Two US lawmakers want American troops out of Pakistan (alternet.org)

Zardari struggling to gain respect of his country men

Unlike the rest of the world where dog is considered a man’s best friend, in Pakistan and some Arab countries dogs are vilified and hated. It is also the term used as an adjective with the name of a hated politician or a high-ranking military official. General Ayub Khan, General Zia, General Musharraf, and a whole host of Pakistani politicians have seen the term “kutta” (dog) attached to their names when their popularity graph took a nosedive.

With the internet, one can in fact see how politicians are viewed by the masses. The current President of Pakistan, Asif Ali Zardari, serves an interesting example. When I reviewed the terms used to search Mr. Zardari on the Google search engine in the past 12 months, the following list turned up.

While the first few entries are variations of his name, the fourth one on the list is the most important one where you could see the derogatory suffix attached to Mr. Zardari’s name. Of course there are other references to the jokes that circulated the net in the past prompting Mr. Zardari’s loyalist legislators to introduce a law that would ban making jokes about Mr. Zardari.

Mr. Zardari assumed the leadership of Pakistan Peoples Party after the death of his wife, Benazir Bhutto, in December 2007. The initial years, i.e., 2008 and 2009, suggest that Mr. Zardari had not yet fallen out of favour for the internet savvy in Pakistan. The searches conducted in 2008 did not make any reference to jokes that had started to circulate the net. By 2009, however, the internet users in Pakistan were searching for “funny Zardari”, which the President obviously did not find funny at all.

|  |

It appears that the term “Zardari Kutta” gained currency in October 2009 and continued to gain in popularity until July 2010.

Politics in Pakistan is a dangerous affair. Pakistan’s political machine is unforgiving and cruel where politicians have lost credibility, money and even life. There is no reason to abandon respect in political debate. This lesson is lost on both politicians and the masses in Pakistan. Venting anger should have better channels in Pakistan than the convention of name calling.

Friday, July 23, 2010

Pakistani prisons continue to hold innocents

More on this from BBC:

Mentally-ill Pakistan 'blasphemer' is released

By M Ilyas Khan BBC News, Islamabad

Blasphemy is an emotive issue in PakistanA court in Pakistan has ordered the release of a mentally-ill woman who was charged with desecrating the Koran, the Muslim holy book, in 1996.

Zaibun Nisa, 60, was never put on trial and her relatives did not contest her arrest, her lawyer said.

Pakistan's blasphemy law prescribes the death sentence for anyone found guilty of insulting the Prophet Muhammad or the Koran.

Human rights groups have been campaigning for its repeal.

They say that the legal procedures involved are weighed against those accused of blasphemy.

On Monday, unidentified gunmen killed two brothers accused of blasphemy in the premises of a Pakistani court.

Public backlash"Zaibun Nisa was declared mentally ill by a medical board soon after her arrest in 1996, but she was still sent to jail," her lawyer, Aftab Ahmad Bajwa, told the media after the court orders on Thursday.

"There was no evidence linking her to the crime," he said.

A police official, requesting anonymity, said she was arrested to defuse the tension - but everyone forgot about her when she was sent to jail.

Her family did not pursue the case probably due to fear of a public backlash, he said.

In Pakistan, people accused of blasphemy and their family members have often been lynched or killed by mobs.

The complainant in the case was Qari Hafeez, a cleric from Lahore who reported to the police that he had found torn pages of the Koran thrown in a drain.

The police lodged a complaint against unknown offenders.

'Mental sub-jail'Qari Hafeez told the media in Lahore on Thursday he did not name Zaibun Nisa as an offender in the case.

"Police acted on their own initiative to arrest the woman," he said.

Mr Bajwa discovered her in a "mental sub-jail" a year ago and filed a petition on her behalf in the Lahore High Court.

He said the woman will be sent to a shelter for homeless people as her family cannot be traced.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

Suicide bombers have killed 5,550 and injured over 7,000 in Pakistan

| Year | Civilians | Security Forces | Terrorists | Total |

| 2003 | 140 | 24 | 25 | 189 |

| 2004 | 435 | 184 | 244 | 863 |

| 2005 | 430 | 81 | 137 | 648 |

| 2006 | 608 | 325 | 538 | 1471 |

| 2007 | 1523 | 597 | 1479 | 3599 |

| 2008 | 2155 | 654 | 3906 | 6715 |

| 2009 | 2307 | 1011 | 8267 | 11585 |

| Total | 7,598 | 2,876 | 14,596 | 25,070 |

Shiites continue to be murdered in Pakistan

The Sunni extremists in Pakistan’s tribal areas have yet again murdered 18 more Shiites in cold blood. The state in Pakistan has become a silent spectator in this game of death where the militant Sunnis, who once were backed by the Pakistani State and still enjoy the blessing of numerous state institutions, continue to kill Shiites and other religious minorities in Pakistan with impunity.

The latest violence has killed 18 Shiites from Kurram Agency in Pakistan’s tribal areas. Hundreds if not thousands of Shiite residents of Kurram Agency have been killed the Sunni extremists since the mid seventies when the American and Saudi-funded Arab and Afghans launched a civil war in Afghanistan.

More from BBC below.

Militants kill 16 in Pakistan convoy ambush

A suspected sectarian attack on a civilian convoy in a troubled tribal area of Pakistan has left 16 dead.

Several other people were wounded in the ambush in the north west, where the army has carried out operations against Islamist militants.

The convoy, which was being escorted by security forces, was attacked in Char Khel village in the Kurram region.

All those killed were Shia Muslims, according to local officials, who said the death toll may rise.

The convoy was heading from Parachinar, in Kurram, to the main regional city of Peshawar when it was ambushed on Saturday in the predominantly Sunni region.

The Kurram tribal district has been a flashpoint for violence between the minority Shias and the Sunni community for several years.

Some reports put the number of dead at 18, including two women.

Jamshed Tori, who was wounded in the attack, told the Reuters news agency: "Militants attacked the last two vehicles in the convoy with automatic weapons near Char Khel village, killing 18 people."

A tribal leader, Mussrat Bangash, also confirmed the deaths.

Kurram has been hit by scores of attacks, including robberies and kidnappings for ransom, in the past three years.

The army has reportedly killed nearly 100 militants in operations in the region, close to the Afghan border, in recent months.

Several major suicide attacks have hit Pakistan in recent weeks. An attack on Thursday killed at least five people in the Swat Valley, also in north west.

Earlier this month, a pair of suicide bombers blew themselves up in the Mohmand tribal region, killing more than 100 people.

The Pakistani government is under US pressure to crack down on the unrest in the border region.

The Shia minority accounts for some 20% of Pakistan's population of 160 million.

More than 4,000 people have died as a result of sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shias since the late 1980s.

Friday, July 9, 2010

50-plus killed in a tribal village in Pakistan

The violence perpetrated by the Sunni extremists is now becoming indiscriminate. In a remote tribal village in the Mohmund tribal region, Sunni extremists killed almost 55 other like-minded Sunnis who may have sided with the government in enforcing law and order.

The victims of such violence in the past were Muslims belonging to the minority sects, such as Shiites and Ahmadis, or progressive Sunnis (Brelvis). In the tribal region, however, many Deobandi Sunnis have fallen victim to the senseless violence perpetrated by the Saudi-inspired extremist Sunnis in Pakistan.

Another very sad day in Pakistan where the most disenfranchised became victims of senseless violence yet again.

Monday, July 5, 2010

What’s wrong with the Afghan strategy?

William Dalrymple writing in the New Statesman explains the flaws in the NATO’s Afghan strategy that relies on a puppet government, which does not enjoy the support of ordinary Afghans.

-----

Why the Taliban is winning in Afghanistan

Published 22 June 2010

As Washington and London struggle to prop up a puppet government over which Hamid Karzai has no control, they risk repeating the blood-soaked 19th-century history of Britain’s imperial defeat.

In 1843, shortly after his return from Afghanistan, an army chaplain, Reverend G R Gleig, wrote a memoir about the First Anglo-Afghan War, of which he was one of the very few survivors. It was, he wrote, "a war begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity, brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it. Not one benefit, political or military, has Britain acquired with this war. Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated."

It is difficult to imagine the current military adventure in Afghanistan ending quite as badly as the First Afghan War, an abortive experiment in Great Game colonialism that slowly descended into what is arguably the greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the west in the Middle East: an entire army of what was then the most powerful military nation in the world utterly routed and destroyed by poorly equipped tribesmen, at the cost of £15m (well over £1bn in modern currency) and more than 40,000 lives. But nearly ten years on from Nato's invasion of Afghanistan, there are increasing signs that Britain's fourth war in the country could end with as few political gains as the first three and, like them, terminate in an embarrassing withdrawal after a humiliating defeat, with Afghanistan yet again left in tribal chaos and quite possibly ruled by the same government that the war was launched to overthrow.

Certainly it is becoming clearer than ever that the once-hated Taliban, far from being swept away by General Stanley McChrystal's surge, are instead regrouping, ready for the final act in the history of Hamid Karzai's western-installed puppet government. The Taliban have now advanced out of their borderland safe havens to the very gates of Kabul and are surrounding the capital, much as the US-backed mujahedin once did to the Soviet-installed regime in the late 1980s. Like a rerun of an old movie, all journeys by non-Afghans out of the capital are once again confined largely to tanks, military convoys and helicopters. The Taliban already control more than 70 per cent of the country, where they collect taxes, enforce the sharia and dispense their usual rough justice. Every month, their sphere of influence increases. According to a recent Pentagon report, Karzai's government has control of only 29 out of 121 key strategic districts.

Just recently, on 17 May, there was a suicide attack on a US convoy in the Dar-ul Aman quarter of Kabul, killing 12 civilians and six American soldiers; the following day, there was a daring five-hour-long grenade and machine-gun assault on the US military headquarters at Bagram Airbase, killing an American contractor and wounding nine soldiers, so bringing the death toll for US armed forces in the country to more than 1,000. Then, over the weekend of 22-23 May, there was a series of rocket, mortar and ground assaults on Kandahar Airbase just as the British ministerial delegation was about to visit it, forcing William Hague and Liam Fox to alter their schedule. Since then, a dozen top Afghan officials have been assassinated in Kandahar, including the city of Kandahar's deputy mayor. On 7 June, the deadliest day for Nato forces in months, ten soldiers were killed. Finally, it appears that the Taliban have regained control of the opium-growing centre of Marjah in Helmand Province, only three months after being driven out by McChrystal's forces amid much gung-ho cheerleading in the US media. Afghanistan is going down.

Already, despite the presence of huge numbers of foreign troops, it is now impossible - or at least extremely foolhardy - for any westerner to walk around the capital, Kabul, without armed guards; it is even more inadvisable to head out of town in any direction except north: the strongly anti-Taliban Panjshir Valley, along with the towns of Mazar-e-Sharif and Herat, are the only safe havens left for westerners in the entire country. In all other directions, travel is possible only in an armed convoy.

This is especially true of the Khord-Kabul and Tezeen passes, immediately to the south of Kabul, where as many as 18,000 British troops were lost in 1842, and which are today again a centre of resistance against perceived foreign occupiers. Aid workers familiar with Afghanistan over several decades say the security situation has never been worse. Ideas much touted only a few years ago that Afghanistan might become a popular tourist destination - a Switzerland of central Asia - now seem to be dreams from a distant age. Lonely Planet's guidebook to Afghanistan, optimistically published in 2005, has not been updated and is now once again out of print.

The present war is following a trajectory that is beginning to feel unsettlingly familiar to students of the Great Game. In 1839, the British invaded Afghanistan on the basis of sexed-up intelligence about a non-existent threat: information about a single Russian envoy to Kabul was manipulated by a group of ambitious and ideologically driven hawks to create a scare - in this case, about a phantom Russian invasion - thus bringing about an unnecessary, expensive and entirely avoidable war.

Initially, the hawks were triumphant - the British conquest proved remarkably easy and bloodless; Kabul was captured within a few weeks as the army of the previous regime melted into the hills, and a pliable monarch, Shah Shuja, was successfully placed on the throne. For a few months the British played cricket, went skating and put on amateur theatricals as if on summer leave in Simla; there were discussions about making Kabul the summer capital of the Raj. Then an insurgency began and that first heady success slowly unravelled, first among the Pashtuns of Kandahar and Helmand Provinces. It slowly gained momentum, moving northwards until it reached Kabul, so making the British occupation impossible to sustain.

What happened next is a warning of how bad things could yet become: a full-scale rebellion against the British broke out in Kabul, and the two most senior British envoys, Sir Alexander Burnes and Sir William Macnaghten, were assassinated, one hacked to death by a mob in the streets, the other stabbed and shot by the resistance leader Wazir Akbar Khan during negotiations. It was on the retreat that followed, on 6 January 1842, that the 18,000 East India Company troops, and maybe half that many again Indian camp followers, were slaughtered by Afghan marksmen waiting in ambush amid the high passes, shot down as they trudged through the icy depths of the Afghan winter. After eight days on the death march, the last 50 survivors made their final stand at the village of Gandamak. As late as the 1970s, fragments of Victorian weaponry and military equipment could be found lying in the screes above the village. Even today, the hill is said to be covered with the bleached bones of the British dead.

One Englishman lived to tell the tale of that last stand (if you discount the fictional survival of Flashman) - an ordinary foot soldier, Thomas Souter, wrapped his regimental colours around him to prevent them being captured, and was taken hostage by the Afghans who assumed that such a colourfully clothed individual must command a high ransom. It is a measure of the increasingly pertinent parallels between the 19th-century war and today's that one of the main Nato bases in Afghanistan was recently named Camp Souter after that survivor.

In the years that followed, the British defeat in Afghanistan became pregnant with symbolism. For the Victorian British, it was the country's greatest imperial disaster of the 19th century. It was exactly a century before another army would be lost, in Singapore in 1942. Yet the retreat from Kabul also became a symbol of gallantry against the odds: William Barnes Wollen's celebrated oil painting The Last Stand of the 44th Regiment at Gundamuck - showing a group of ragged but doggedly determined British soldiers standing encircled behind a porcupine of bayonets, as the Pashtun tribesmen close in - became one of the best-known images of the era, along with Remnants of an Army, Elizabeth Butler's image of the wounded and bleeding army surgeon William Brydon, who had made it through to the safety of Jalalabad, arriving before the city walls on his collapsing nag.

For the Afghans, the British defeat of 1842 became a symbol of freedom from foreign invasion. It is again no accident that the diplomatic quarter of Kabul is named after the general who oversaw the rout of the British in that year: Wazir Akbar Khan.

For south Asians, who provided most of the cannon fodder - the foot soldiers and followers killed on the retreat - the war ironically became a symbol of possibility: although thousands of Indians died on the march, it showed that the British army was not invincible and a well-planned insurgency could force them out. Thus, in 1857, the Indians launched their own anti-colonial uprising, the Great Mutiny (as it is known in Britain) or the first war of independence (as it is known in India), partly inspired by what the Afghans had achieved in 1842.

This destabilising effect on south Asia of the failed war in Afghanistan has a direct parallel in the blowback that is today destabilising Pakistan and the tribal territories of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata). Here the Pakistani Taliban are once more on the march, rebuilding their presence in Swat, and are now surrounding Peshawar, which is almost daily being rocked by bombs, while outlying groups of Taliban are again spreading their influence into the valleys leading towards Islamabad. Across much of the North-West Frontier Province - roughly a fifth of Pakistan's territory - women have now been forced into the burqa, music has been silenced, barbershops are forbidden to shave beards and more than 125 girls' schools have been blown up or burned down.

A significant proportion of the Peshawar elite, along with the city's musicians, have decamped to the relatively safe and tolerant confines of Lahore and Karachi, while tens of thousands of ordinary people from the surrounding hills of the semi-autonomous Fata tribal belt, and especially the Bajaur Agency (or tribal area), have fled from the conflict zones blasted by US Predator drones and strafed by Pakistani helicopter gunships to the tent camps ringing the provincial capital.

The Fata, it is true, have never been fully under the control of any Pakistani government, and have always been unruly, but the region has been radicalised as never before by the rain of shells and cluster bombs that have caused huge civilian casualties and daily add a stream of angry foot soldiers to the insurgency. Elsewhere in Pakistan, anti-western religious and political extremism continues to flourish, as ever larger numbers of ordinary Pakistanis are driven to fight by corruption, predatory politics and the abuse of power by Pakistan's feudal elite, as well as the military aggression of the drones. Indeed, the ripples of instability lapping out from Afghanistan and Pakistan have reached even New York. When CIA interrogators asked Faisal Shahzad why he tried to let off a car bomb last month in Times Square, he told them of his desire to avenge those "innocent people being hit by drones from above".

The route of the British retreat of 1842 backs on to the mountain range that leads to Tora Bora and the Pakistan border, an area that has always been a Taliban centre. I had been advised not to attempt to visit the area without local protection, and so last month I set off for the mountains in

the company of a regional tribal leader who was also a minister in Karzai's government. He is a mountain of a man named Anwar Khan Jegdalek, a former village wrestling champion who made his name as a Hezb-e-Islami mujahedin commander in the jihad against the Soviets in the 1980s.It was Anwar Khan Jegdalek's ancestors who inflicted some of the worst casualties on the British army of 1842, something he proudly repeated several times as we drove through the same passes. "They forced us to pick up guns to defend our honour," he said. "So we killed every last one of those bastards." None of this, incidentally, has stopped Anwar Khan Jegdalek from sending his family away from Kabul to the greater safety of Northolt, Middlesex.

He drove himself in a huge 4x4, while a pick-up full of heavily armed Afghan bodyguards followed behind. We left Kabul - past the blast walls of the Nato barracks built on the very site of the British cantonment of 170 years ago - and headed down a corkscrewing road into the line of bleak mountain passes that links Kabul with the Khyber Pass.

It is a dramatic and violent landscape: fault lines of crushed and tortured strata groaned and twisted in the gunpowder-coloured rock walls rising on either side of us. Above, the jagged mountain tops were veiled in an ominous cloud of mist. As we drove, Anwar Khan Jegdalek complained bitterly of western treatment of his government. "In the 1980s when we were killing Russians for them, the Americans called us freedom fighters," he muttered, as we descended through the first pass. "Now they just dismiss us as warlords."

At Sorobi, where the mountains debouche into a high-altitude ochre desert dotted with encampments of nomads, we left the main road and headed into Taliban territory. A further five trucks full of Anwar Khan Jegdalek's old mujahedin fighters, all brandishing rocket-propelled grenades and with faces wrapped in keffiyehs, appeared from a side road to escort us.

At the crest of Jegdalek village, on 12 January 1842, 200 frostbitten British soldiers found themselves surrounded by several thousand Pashtun tribesmen. The two highest-ranking British soldiers, General Elphinstone and Brigadier Shelton, went off to negotiate but were taken hostage. Only 50 infantrymen managed to break out under cover of darkness. Our own welcome was, thankfully, somewhat warmer. It was my host's first visit to his home since he had become a minister, and the proud villagers took their old commander on a nostalgia trip through hills smelling of wild thyme and rosemary, and up on to mountainsides carpeted with hollyhocks, mulberries and white poplars. Here, at the top of the surrounding peaks, lay the remains of Anwar Khan Jegdalek's old mujahedin bunkers and entrenchments. Once the tour was completed, the villagers fed us, Mughal style, in an apricot orchard: we sat on carpets under a trellis of vine and pomegranate blossom as course after course of kebabs and mulberry pulao was laid in front of us.

During lunch, as my hosts casually pointed out the various places in the village where the British had been massacred in 1842, I asked them if they saw any parallels between that war and the present situation. "It is exactly the same," said Anwar Khan Jegdalek. "Both times the foreigners have come for their own interests, not for ours. They say, 'We are your friends, we want democracy, we want to help.' But they are lying."

“Whoever comes to Afghanistan, even now, they will face the fate of Burnes, Macnaghten and Dr Brydon," said Mohammad Khan, our host in the village and the owner of the orchard where we were sitting. The names of the fighters of 1842, long forgotten in their home country, were still known here.

“Since the British went, we've had the Russians," said an old man to my right. "We saw them off, too, but not before they bombed many of the houses in the village." He pointed at a ridge of ruined mud-brick houses.

“We are the roof of the world," said Mohammad Khan. "From here, you can control and watch everywhere."

“Afghanistan is like the crossroads for every nation that comes to power," agreed Anwar Khan Jegdalek. "But we do not have the strength to control our own destiny - our fate is always determined by our neighbours. Next, it will be China. This is the last days of the Americans."

I asked if they thought the Taliban would come back. "The Taliban?" said Mohammad Khan. "They are here already! At least after dark. Just over that pass." He pointed in the direction of Gandamak and Tora Bora. "That is where they are strongest."

It was nearly five in the afternoon before the final flaps of nan bread were cleared away, by which time it had become clear that it was too late to head on to the site of the British last stand at Gandamak. Instead, that evening we went to the relative safety of Jalalabad, where we discovered we'd had a narrow escape: it turned out there had been a huge battle at Gandamak that morning between government forces and a group of villagers supported by the Taliban. The sheer scale and length of the feast had saved us from walking straight into an ambush. The battle had taken place on exactly the site of the British last stand.

The following morning in Jalalabad, we went to a jirga, or assembly of tribal elders, to which the greybeards of Gandamak had come under a flag of truce to discuss what had happened the day before. The story was typical of many I heard about the current government, and revealed how a mixture of corruption, incompetence and insensitivity has helped give an opening for the return of the once-hated Taliban.

As Predator drones took off and landed incessantly at the nearby airfield, the elders related how the previous year government troops had turned up to destroy the opium harvest. The troops promised the villagers full compensation, and were allowed to burn the crops; but the money never turned up. Before the planting season, the villagers again went to Jalalabad and asked the government if they could be provided with assistance to grow other crops. Promises were made; again nothing was delivered. They planted poppy, informing the local authorities that if they again tried to burn the crop, the village would have no option but to resist. When the troops turned up, about the same time as we were arriving at nearby Jegdalek, the villagers were waiting for them, and had called in the local Taliban to assist. In the fighting that followed, nine policemen were killed, six vehicles destroyed and ten police hostages taken.

After the jirga was over, one of the tribal elders came over and we chatted for a while over a glass of green tea. "Last month," he said, "some American officers called us to a hotel in Jalalabad for a meeting. One of them asked me, 'Why do you hate us?' I replied, 'Because you blow down our doors, enter our houses, pull our women by the hair and kick our children. We cannot accept this. We will fight back, and we will break your teeth, and when your teeth are broken you will leave, just as the British left before you. It is just a matter of time.'"

What did he say to that? “He turned to his friend and said, 'If the old men are like this, what will the younger ones be like?' In truth, all the Americans here know that their game is over. It is just their politicians who deny this."

The defeat of the west's latest puppet government on the very same hill of Gandamak where the British came to grief in 1842 made me think, on the way back to Kabul, about the increasingly close parallels between the fix that Nato is in and the one faced by the British 170 years ago.

Now as then, the problem is not hatred of the west, so much as a dislike of foreign troops swaggering around and making themselves odious to the very people they are meant to be helping. On the return journey, as we crawled back up the passes towards Kabul, we got stuck behind a US military convoy of eight Humvees and two armoured personnel carriers in full camouflage, all travelling at less than 20 miles per hour. Despite the slow speed, the troops refused to let any Afghan drivers overtake them, for fear of suicide bombers, and they fired warning shots at any who attempted to do so. By the time we reached the top of the pass two hours later, there were 300 cars and trucks backed up behind the convoy, each one full of Afghans furious at being ordered around in their own country by a group of foreigners. Every day, small incidents of arrogance and insensitivity such as this make the anger grow.

There has always been an absolute refusal by the Afghans to be ruled by foreigners, or to accept any government perceived as being imposed on the country from abroad. Now as then, the puppet ruler installed by the west has proved inadequate to the job. Too weak, unpopular and corrupt to provide security or development, he has been forced to turn on his puppeteers in order to retain even a vestige of legitimacy in the eyes of his people. Recently, Karzai has accused the US, the UK and the UN of orchestrating a fraud in last year's elections, described Nato forces as "an army of occupation", and even threatened to join the Taliban if Washington kept putting pressure on him. Shah Shuja did much the same thing in 1842, towards the end of his rule, and was known to have offered his allegiance and assistance to the insurgents who eventually toppled and beheaded him.

Now as then, there have been few tangible signs of improvement under the western-backed regime. Despite the US pouring approximately $80bn into Afghanistan, the roads in Kabul are still more rutted than those in the smallest provincial towns of Pakistan. There is little health care; for any severe medical condition, patients still have to fly to India. A quarter of all teachers in Afghanistan are themselves illiterate. In many areas, district governance is almost non-existent: half the governors do not have an office, more than half have no electricity, and most receive only $6 a month in expenses. Civil servants lack the most basic education and skills.

This is largely because $76.5bn of the $80bn committed to the country has been spent on military and security, and most of the remaining $3.5bn on international consultants, some of whom are paid in excess of $1,000 a day, according to an Afghan government report. This, in turn, has had other negative effects. As in 1842, the presence of large numbers of well-paid foreign troops has caused the cost of food and provisions to rise, and living standards to fall. The Afghans feel they are getting poorer, not richer.

There are other similarities. Then as now, the war effort was partially privatised: it was not so much the British army as a corporation, the East India Company, that provided most of the troops who fought the war for Britain in 1842, just as today both the British and the Americans have subcontracted much of their security work to private companies. When I visited the British embassy, I found that many of the security guards at the gatehouse were not army or military police, but from Group 4 Security. The US security contracts offered to Blackwater/Xe and other private security forces under Dick Cheney's ideologically driven policy of privatising war are worth many millions of dollars.

Finally, now as then, there has been an attempt at a last show of force in order to save face before withdrawal. As happened in 1842, it has achieved little except civilian casualties and the further alienation of the Afghans. As one of the tribal elders from Jegdalek said to me: "How many times can they apologise for killing our innocent women and children and expect us to forgive them? They come, they bomb, they kill us and then they say, 'Oh, sorry, we got the wrong people.' And they keep doing that."

The British soldiers of 1842 found the same reaction in their day. In his diary of his time with the British army of retribution, which laid waste to great areas of southern Afghanistan as punishment for the massacres on the retreat from Kabul earlier in the year, the young Captain N Chamberlain reported how his troops inflicted horrible atrocities on any Afghan civilians they could find. One morning he met a wounded Afghan woman dragging herself towards a stream with a water pot. "I filled the vessel for her," he wrote, "but all she said was, 'Curses on the feringhees [foreigners]!' I continued on my way disgusted with myself, the world, above all with my cruel profession. In fact, we are nothing but licensed assassins."

However, there are some important differences between Britain's first defeat in Afghanistan and the current mess. In 1842, we were at least reinstalling a legitimate Afghan ruler and removing one who could genuinely be cast as an illegitimate usurper. Shah Shuja, the British puppet, was a former ruler of the Sadozai dynasty, from the leading Pashtun clan, and a grandson of the great Ahmed Shah Durrani, the first king of a united Afghanistan. As the traveller and pioneering archaeologist Charles Masson observed: "The Afghans had no objection to the match; they merely disliked the manner of the wooing."

This time, we have been clumsier, and Nato has helped instal a former CIA asset accused by a high-ranking UN diplomat of drug abuse and of having a history of mental instability, with little to recommend him other than that he was once run out of Langley. Although Karzai is a Pashtun of the Popalzai tribe, under his watch Nato has in effect installed the Northern Alliance in Kabul and driven the country's Pashtun majority out of power.

The reality of our present Afghan entanglement is that we took sides in a complex civil war, which has been running since the 1970s, siding with the north against the south, town against country, secularism against Islam, and the Tajiks against the Pashtuns. We have installed a government, and trained up an army, both of which in many ways have discriminated against the Pashtun majority, and whose top-down, highly centralised constitution allows for remarkably little federalism or regional representation. However much western liberals may dislike the Taliban - and they have very good reason for doing so - the truth remains that they are in many ways the authentic voice of rural Pashtun conservatism, whose views and wishes are ignored by the government in Kabul and who are still largely excluded from power. It is hardly surprising that the Pashtuns are determined to resist the regime and that the insurgency is widely supported, especially in the Pashtun heartlands of the south and east.

Yet it is not too late to learn some lessons from the mistakes of the British in 1842. Then, British officials in Kabul continued to send out despatches of delusional optimism as the insurgents moved ever closer to Kabul, believing that there was a straightforward military solution to the problem and that if only they could recruit enough Afghans to their army, they could eventually march out, leaving that regime in place - exactly the sentiments expressed by the Defence Secretary, Liam Fox, on his visit to Afghanistan last month.

In 1842, by the time they realised they had to negotiate a political solution, their power had ebbed too far, and the only thing the insurgents were willing to negotiate was an unconditional surrender. Today, too, there is no easy military solution to Afghanistan: even if we proceed with the plan to equip an army of half a million troops (at the cost of roughly $2bn a year, when the entire revenue of the Afghan government is $1.1bn - in other words, 180 per cent of revenue), that army will never be able to guarantee security or shore up such a discredited regime. Every day, despite the military power of the US and Nato and the $25bn so far ploughed into rebuilding the Afghan army, security gets worse, and the area under government control contracts week by week.

The only answer is to negotiate a political solution while we still have enough power to do so, which in some form or other involves talking to the Taliban. This is a course that Karzai, to his credit, is keen to pursue; he made it clear that his peace jirga at the start of this month was open to any Taliban leader willing to lay down arms, and that jobs and monetary incentives would be available to former Taliban who changed their allegiance and joined the government. It is still unclear whether the new Tory government supports this course; Barack Obama certainly opposes it. In this, he is supported by the notably undiplomatic US envoy to the region, Richard Holbrooke, described by one senior British diplomat as "a bull who brings his own china shop wherever he goes".

There is something else we can still do before we pull out: leave some basic infrastructure behind, a goal we notably failed to achieve in the past nine years. Yet William Hague and Liam Fox oppose this policy - as Fox notoriously said in his 21 May interview with the Times, which infuriated his Afghan hosts: "We are not in Afghanistan for the sake of the education policy in a broken 13th-century country." The Tories could do much worse than consult their own newly elected backbencher Rory Stewart. He knows much more about Afghanistan than either Fox or Hague. As Stewart wrote shortly before he entered politics, targeted aid projects that employ Afghans can do a great deal of good, "and we should focus on meeting the Afghan government's request for more investment in agriculture, irrigation, energy and roads".

In the meantime, Obama has announced that he will begin withdrawing troops in July 2011. The start of the US withdrawal is likely to begin a rush to evacuate the other Nato forces located in pockets around the country: the Dutch have announced that they will be pulling out of Uruzgan this summer, and the Canadian and Danes won't be far behind them. Nor will the Brits, despite assurances from Hague and Fox. A recent poll showed that 72 per cent of Britons want their troops out of Afghanistan immediately, and there is only so long any government can hold out against such strong public opinion. Certainly, it is time to shed the idea that a pro-western puppet regime that excludes the Pashtuns can remain in place indefinitely. The Karzai government is crumbling before our eyes, and if we delude ourselves that this is not the case, we could yet face a replay of 1842.

George Lawrence, a veteran of that war, issued a prescient warning in the Times just before Britain blundered into the Second Anglo-Afghan War in the 1870s. "A new generation has arisen which, instead of profiting from the solemn lessons of the past, is willing and eager to embroil us in the affairs of that turbulent and unhappy country," he wrote. "Although military disasters may be avoided, an advance now, however successful in a military point of view, would not fail to turn out to be as politically useless."

William Dalrymple's latest book, "Nine Lives: in Search of the Sacred in Modern India", won the first Asia House Literary Award in May, and is newly published in paperback (Bloomsbury, £8.99). His book on the First Anglo-Afghan War is planned for release in autumn 2012